4.2 Synthesizing literature

Learning Objectives

- Connect the sources you read with key concepts in your research question and proposal

- Systematize the information and facts from each source you read

Putting the pieces together

Combining separate elements into a whole is the dictionary definition of synthesis. It is a way to make connections among numerous and varied source materials. A literature review is not organized by author, title, or date of publication like an annotated bibliography. Rather, it is grouped by topic and argument to create a whole view of the literature relevant to your research question.

Your synthesis must demonstrate a critical analysis of the papers you collected, as well as your ability to integrate the results of your analysis into your own literature review. Each source you collect should be critically evaluated and weighed based on the criteria from Chapter 3 before you include it in your review.

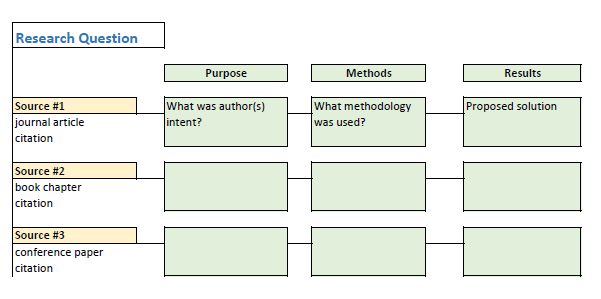

Begin the synthesis process by creating a grid, table, or an outline where you will summarize your literature review findings, using common themes you have identified and the sources you have found. The summary, grid, or outline will help you compare and contrast the themes, so you can see the relationships among them as well as areas where you may need to do more searching. A basic summary table is provided in Figure 4.2. Whichever method you choose, this type of organization will help you to both understand the information you find and structure the writing of your review. Remember, although “the means of summarizing can vary, the key at this point is to make sure you understand what you’ve found and how it relates to your topic and research question” (Bennard et al., 2014, para. 10). [1]

As you read through the material you gather, look for common themes as they may provide the structure for your literature review. Remember, it is not unusual to go back and search academic databases for more sources of information as you read the articles you’ve already collected.

Literature reviews can be organized sequentially or by topic, theme, method, results, theory, or argument. It’s important to develop categories that are meaningful and relevant to your research question. Take detailed notes on each article and use a consistent format for capturing all the information each article provides. These notes and the summary table can be done manually using note cards. However, given the amount of information you will be recording, an electronic file created in a word processing or spreadsheet is more manageable. Examples of fields you may want to capture in your notes include:

- Authors’ names

- Article title

- Publication year

- Main purpose of the article

- Methodology or research design

- Participants

- Variables

- Measurement

- Results

- Conclusions

Other fields that will be useful when you begin to synthesize the sum of your research include:

- Specific details of the article or research that are especially relevant to your study

- Key terms and definitions

- Statistics

- Strengths or weaknesses in research design

- Relationships to other studies

- Possible gaps in the research or literature (for example, many research articles conclude with the statement “more research is needed in this area”)

- Finally, note how closely each article relates to your topic. You may want to rank these as high, medium, or low relevance. For papers that you decide not to include, you may want to note your reasoning for exclusion, such as small sample size, local case study, or lacks evidence to support conclusions.

An example of how to organize summary tables by author or theme is shown in Table 4.1.

| Author/Year | Research Design | Participants or Population Studied | Comparison | Outcome |

| Smith/2010 | Mixed methods | Undergraduates | Graduates | Improved access |

| King/2016 | Survey | Females | Males | Increased representation |

| Miller/2011 | Content analysis | Nurses | Doctors | New procedure |

For a summary table template, see http://blogs.monm.edu/writingatmc/files/2013/04/Synthesis-Matrix-Template.pdf

Creating a topical outline

An alternative way to organize your articles for synthesis it to create an outline. After you have collected the articles you intend to use (and have put aside the ones you won’t be using), it’s time to extract as much as possible from the facts provided in those articles. You are starting your research project without a lot of hard facts on the topics you want to study, and by using the literature reviews provided in academic journal articles, you can gain a lot of knowledge about a topic in a short period of time.

As you read an article in detail, I suggest copying the information you find relevant to your research topic into a separate word processing document. However, you will find that copying and pasting from PDF to Word can be a pain because PDFs are image files not documents. To make that easier, use the HTML version of the article, convert the PDF to Word in Adobe Acrobat or another PDF reader, or use “paste special” command to paste the content into Word without formatting. If it’s an old PDF, you may have to simply type out the information you need. It can be a messy job, but having all of your facts in one place is very helpful for drafting your literature review.

When making your notes document, you should copy and paste any fact or argument you consider important, such as definitions of concepts, statistics about the size of the social problem, and empirical evidence about the key variables in the research question, among countless others. It’s a good idea to consult with your professor and the syllabus for the course about what they are looking for when they read your literature review. Facts for your literature review are principally found in the introduction, results, and discussion section of an empirical article or at any point in a non-empirical article. Again, any information you may want to use in your literature review should go into your notes document.

During this process, it is imperative that you cite the original article or source that the information came from. This way, you will not make the mistake of plagiarizing when you use these notes to write your research paper and you will be able to refer to the article with ease. Nothing is worse than pulling facts from your notes, only to realize that you forgot to note where those facts came from. In addition, if you found a statistic that the author used in the introduction, it almost certainly came from another source that the author cited in a footnote or internal citation. You will want to check the original source to make sure the author represented the information correctly as well as cite the original, primary source of that statistic. Moreover, you may want to read the original study to learn more about your topic and discover other sources relevant to your inquiry.

Assuming you have pulled all of the facts out of multiple articles, it’s time to start thinking about how these pieces of information relate to each other. Start grouping each fact into categories and subcategories as shown in Figure 4.3. For example, a statistic stating that homeless single adults are more likely to be male may fit into a category of gender and homelessness. For each topic or subtopic you identified during your critical analysis of each paper, determine what those papers have in common. Likewise, determine which ones in the group differ. If there are contradictory findings, you may be able to identify methodological or theoretical differences that could account for the contradiction. For example, one study may sample only high-income earners or those in a rural area. Determine what general conclusions you can report about the topic or subtopic, based on all of the information you’ve found.

I suggest creating a separate document containing a topical outline to combine your facts from each source and organize them by topic or category. As you include more facts and more sources into your topical outline, you will begin to see how each fact fits into a category and how categories are related to each other. Your category names may change over time, as may their definitions. This is a natural reflection of the learning you are doing.

| Facts copied from an article | Topical outline: Facts organized by category |

|

|

As you can see, a complete topical outline is a long list of facts, arranged by category about your topic. As you step back from the outline, you should be able to identify the topic areas in which you have gathered sufficient information to draw strong conclusions. You should also be able to identify areas in which you will need to conduct further research to gain a better understanding of the topic. The topical outline should serve as a transitional document between the notes you write on each source and the literature review you submit to your professor.

It is important to note that both the notes document and the topical outline contain plagiarized information that is copied and pasted directly from the primary sources. Not to worry, these are just notes that are meant to guide you and are not being turned in to your professor as your own ideas. To avoid any possibility of plagiarism in your final literature review, you must paraphrase each piece of information and properly attribute it to its primary source. More importantly, you should keep your voice and ideas front-and-center in what you write as this is your analysis of the literature. Make strong claims and support them thoroughly using facts you found in the literature. We will pick up the task of writing your literature review in section 4.3.

Additional resources for synthesizing literature

There are many ways to approach synthesizing literature. We’ve reviewed two examples here: summary tables and topical outlines. Other examples you may encounter include annotated bibliographies and synthesis matrixes. As you are learning research, find a method that works for you. Reviewing the literature is a core component of evidence-based practice in social work at any level. See the resources below if you need some additional help:

Literature Reviews: Using a Matrix to Organize Research / Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota

Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources / Indiana University

Writing a Literature Review and Using a Synthesis Matrix / Florida International University

Sample Literature Reviews Grid / Complied by Lindsay Roberts

Killam, Laura (2013). Literature review preparation: Creating a summary table. Includes transcript. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nX2R9FzYhT0

Key Takeaways

- It is necessary to take notes on research articles as you read. Try to develop a system that works for you to keep your notes organized, such as a summary table.

- Summary tables and topical outlines help researchers synthesize sources for the purpose of writing a literature review.

- Bernnard, D., Bobish, G., Hecker, J., Holden, I., Hosier, A., Jacobson, T., Loney, T., & Bullis, D. (2014). Presenting: Sharing what you’ve learned. In Bobish, G., & Jacobson, T. (eds.) The information literacy users guide: An open online textbook. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/chapter/present-sharing-what-youve-learned/ ↵

- Figure 4.2 copied from Frederiksen, L. & Phelps, S. F. (2018). Literature reviews for education and nursing graduate students. Shared under a CC-BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). ↵

- This table was adapted from the work of Amanda Parsons. For more of Amanda's work see the exemplars for assignments linked in the front matter of this textbook. ↵